THE SILENT FILM ERA

Museum of the Moving Image’s Collection includes more than 5,000 artifacts dating from 1894 to 1931, comprising posters and other promotional material; costumes; glass slides; technical apparatus including motion picture cameras and projectors, editing and laboratory equipment, and lighting; scrapbooks and correspondence; portraits, scene stills, and behind-the-scenes photographs; and oral histories with actors and filmmakers. This uniquely wide-ranging collection offers an unparalleled opportunity to study how silent and early sound films were made, marketed, and exhibited. By some estimates, 80 percent of American silent films are no longer extant, making such material culture holdings particularly significant.

This essay by film historian (and former MoMI curator) Richard Koszarski traces how the period between 1894 and 1931 became defined as the “silent film era,” explores the emergence of the idea of preserving the history of this period through material culture, and describes several key artifacts from this period in MoMI’s Collection.

It is generally said to have begun in 1894, as the first paying customers lined up at a Kinetoscope Parlor showing films made by Thomas Edison near the corner of Broadway and 27th Street in Manhattan, and was certainly over by 1931, when the last of Hollywood's silent features were released by Paramount and United Artists.

Only later would those years be thought of as "the silent film era," and sectioned off as a sort of prelude to the real movies that would follow. But the idea that their favorite new medium might be lacking in something essential had never occurred to audiences of the time. And the businessmen (and artists) who had created this industry were too busy enjoying their newfound fame and fortune to even dream of that sort of a change. As Harry Warner famously said, "Who the hell wants to hear actors talk?"

That was Warner's response to AT&T's offer to go in with them on a talking picture system. An experienced showman, he knew the sorry history of this concept, which one inventor or another was always touting as the next new thing in motion pictures. He also knew the amount of money that had been wasted on such gadgets. And he was right: there was no demand to hear actors speaking from the screen. But Warner saw something else, and did agree to help develop sound films, whose canned musical accompaniments could save the theater-owning brothers a fortune in weekly musicians' salaries. As with many technological innovations— including the internet—the real benefits only became apparent after the system was already in place. And so the notion of a "silent film era" was born.

***

The cinema is both an art and an industry, a curious mix of culture and technology that generations of critics and historians have puzzled over. The art part exists only on screen. By the 1930s a few museums and private collectors had already begun to collect prints of individual film titles, assessing their curatorial value through a range of ad hoc criteria. But the first museum to display its own collection of motion picture artifacts was the Smithsonian Institution, whose Graphic Arts Department began exhibiting film projectors and pre-cinema apparatus in 1897. A few others followed suit, sometimes putting their motion picture materials in the "useful arts" wing, sometimes the technology room, and occasionally even giving them a corner in the photography collection.

Henri Langlois, one of the first film archivists, began to collect motion picture prints in the early 1930s, when he realized that silent films, now economically obsolete, were doomed. Langlois devoted his life to saving silent films, but he soon found himself saving every other film, too. Unlike rival archivists in New York or London, Langlois's criteria were not merely aesthetic, but cultural. He realized that cinema was not simply the part of the show that came in a can, but a complex web of economic, cultural, and technological factors which necessarily involved commerce and industry as well as art. Langlois ultimately tried to have it all, operating both an archive of films (cinematheque) and, for interpretive context, a musée du cinema. A radical policy for any film archive, it meant diverting scarce resources away from film prints in order to collect costumes and posters, movie cameras and theater programs.

Although some supporters criticized this broad-based approach, few historians today would write a history of motion pictures without offering a clear understanding of their cultural and industrial context. Motion picture materials can now be found in dozens of collections all over the world, from theater libraries to science museums. Still, very few have the range of resources, from moviolas to fan magazines, to adequately document the complex role such materials have played in the development of moving image media.

***

An earlier generation of historians, steeped in technological determinism, saw the coming of sound as a watershed, a step in the drive towards "realism" that would make everything that came before it suddenly irrelevant. Talkies did affect one corner of the marketplace, of course, as all those unemployed musicians could testify. But this was evolution, not revolution, and certainly no reason to banish the silent film to some cinematic dark age. As demonstrated by historians from André Bazin to David Bordwell, the introduction of sound was a speed bump, not an apocalypse. The grammar of film—how the camera addresses its subject, and how editors cut shots together—quickly returned to the classic style developed in the 1920s. No Hollywood studios went out of business. The same 35mm film went through the same film projectors (now with added sound heads), while audiences read the same film magazines and attended the same local theaters.

During those few "silent" decades, Edison's invention had developed from a mechanical curiosity to a major international industry, and became—as D. W. Griffith once boasted—the only new art form created since antiquity. No primitive backwater, the years from 1894 to 1931 must have impressed both filmmakers and audiences as an unending stream of innovation and experimentation. Later years may have been dominated by Technicolor and television, but audiences of the 1920s would have wondered just why improvements like these took so long to catch on—since both were already part of the creative mix long before The Jazz Singer (1927).

So while the advertising materials, home movie cameras, film costumes, and licensed merchandise shown here may differ in style from their modern equivalents, the important thing to remember is that their functions remain identical—even in a digital age undreamed of by Harry Warner.

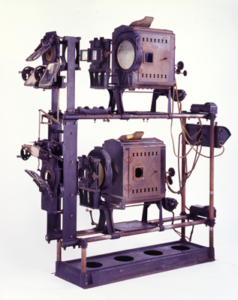

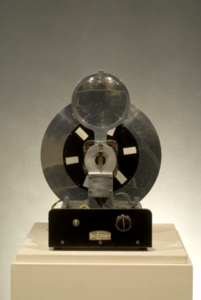

BRENKERT F7 MASTER BRENOGRAPH

Between 1929 and 1930, the Loew's theater chain asserted its dominance of the local motion picture market by opening a ring of five spectacular "wonder theaters" in and around New York. Planned during the silent film era but opened after the triumph of talkies (and in the teeth of the great depression), the wonder theaters would never be equaled in scale and extravagance.

The Brenkert F7 Master Brenograph was an essential part of late picture palace design, but it was not a motion picture projector. Indeed, its manufacturer boasted that it was capable of projecting "Everything But the Film," thus serving a variety of functions unneeded today, but an absolute requirement for every first class picture house at the end of the 1920s.

Audiences did not attend these theaters only (or even principally) to see the newest and best movies. They were attracted by ambiance, décor, specialized stage presentations, the resident orchestra, even the air-conditioning. Theaters competed to attract a regular clientele which could be expected to turn up at least once a week, regardless of the particular film program.

According to the Brenkert Light Projection Co. of Detroit, which introduced the model F7 in 1928, "With the rapid trend to better entertainment and progress in theatre environment the Master Brenograph thoroughly relieves purely picture entertainments of monotony and greatly enhances any entertainment program with results never before obtained in a theatre." It could do this by projecting drifting clouds across the auditorium ceiling and rippling waterfalls wherever the management might wish to see them. While earlier movie theaters had used still image projectors for song slides, local advertisements, or announcements of upcoming programs, the Master Brenograph was designed as an integral part of any picture palace's live stage productions. Complex multi-image presentations involving anything from projected scenery to abstract color patterns could all be easily managed from the booth.

The five wonder theaters, all of which are still standing today, were the Loew's 175th Street in Manhattan, the Paradise in the Bronx, the Valencia in Queens, the Jersey in Jersey City, and the Kings, at Flatbush and Tilden Avenues in Brooklyn. The Brenograph in the Museum's collection was removed from the Loew's Kings in 1991, where it still occupied its dedicated niche in one corner of the derelict projection booth.

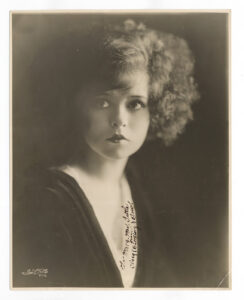

The Kings had opened on September 7, 1929, with the local premiere of Evangeline, a United Artists feature that had already played the Rivoli, on Times Square, back in July. Evangeline was a first class production, but it was not even a full talkie, only a silent movie with two interpolated songs for its star, Dolores del Rio. That very same week, Loew's had opened the Paradise in the Bronx with an all-talking picture. But why did they choose to launch their 3,700 seat Brooklyn showcase with Evangeline?

As Marcus Loew once said, "we sell tickets to theaters, not movies." From his perspective, it made little difference just what film he had on the screen. His audiences came for the added value they had grown to expect from a Loew's presentation, in this case a stage show direct from the Capitol Theatre and a personal appearance by Dolores del Rio herself. After all, who could be sure that the "purely picture entertainment" would really pull in the crowds? That's what the Master Brenograph was for.